The Sleep

of Reason:

Curse of the Demon and the Return of the Gothic Horror Movie.

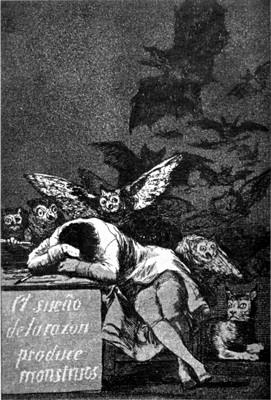

"The Sleep of Reason breeds monsters"--Goya

|

1. The end of World War II saw an end to the great studio era of horror movies. Horror movies didn’t die out--far from it--but the war had introduced horrors and anxieties to which the idiom of the classic horror movie was unequal. The essential fright films of the decade following the war were not horror movies at all, strictly speaking, but were science fiction films like George Pal’s The War of the Worlds, which reduced human beings to the equivalent of dust motes moving through an uncaring cosmos, or even more literally: Jack Arnold's The Incredible Shrinking Man, in which our everyman hero is manouevered into a state of pure existentialism. "I still exist!" he declares to an indifferent universe, even as he has become less than a dust mote. These movies couched their horrors in the awful possibilities of science as demonstrated by the twin catastrophes of the death camps and the atomic bomb. These films offered redemption through reason and science, too--it was science and reason that won the war, a trait sold to the movie-going public as good old-fashioned American know-how. The culture at large was much the same. The post-war era was an era of conformity, an era of prosperity, an era of reason. This was the era of Sputnik and the International Geophysical Year. It was an era when the power of the atom was put to use, when space was the next frontier. It was an era when the old bogeys that haunted the imagination went into remission, chased into ever shrinking shadows by the cold, hard light of science. But, of course, they didn’t stay there for long. The gothic horror film began to reappear as a commercial and artistic force in the second half of the 1950s. The resurgence of the gothic horror film can be attributed to several causes. The sale of the Universal horror films to television to surprisingly high ratings is one possible cause, an audience of teen-agers who grew up reading E. C. comics is another. Small, independent studios were discovering that horror movies were cheap to make and returned a tidy profit from the newly burgeoning drive-in movie circuit. It is also possible that the collision of conformist rationality with monsters from the id simply caused the culture to blow a gasket. The first wave of the revised gothics relied on old formulae--The Hammer horrors that appeared in 1957 were essentially retreads of the Universal horrors that let blood in color, for example--but there was something else in the air that redirected them almost immediately. The new Gothics began to challenge the assumptions that had built the era’s dominant culture. Today, it’s widely thought that the "New Age" movement began in the late sixties with the hippies, but its roots can be seen much earlier. Anton Levay, following in the footsteps of Aleister Crowley and apropos of the horror movies of the period, founded the Church of Satan long before the Summer of Love. The backlash against a deterministic view of the universe--particularly in relation to the horror story--is memorably invoked in the first sentence of Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, originally published in 1959:

2. Jacques Tourneur’s Curse of the Demon, released in 1957, appeared relatively early in the gothic revival of the late fifties. It’s a film that takes the conflict between reason and unreason as its primary theme, even beyond the usual Hammer formula where the forces of chaos are defeated by an upright savant with deep knowledge of the enemy. For all their Manichean dichotomies of good and evil, Hammer pit one form of superstition against another. Their savants were like warrior monks (sometimes literally, as in Dracula: Prince of Darkness (1966)), who often turned black magic against itself (as in Kiss of the Vampire (1963)). Hammer’s gothics were essentially morality plays. Curse of the Demon is different. Curse of the Demon is set in an immediate here and now (or an immediate here and now in 1957) rather than some non-specific past. It examines superstition in the foreground as an object of study in and of itself. More than that, it examines reason in the foreground as an object of study as well, weighing the pros and cons of reason and superstition both in their turn. Nor does it deal in tidy dualities. The questions it asks are multi-faceted, as are the answers it provides. This is something that the film’s producers didn’t understand, as it so happens. Director Jacques Tourneur preferred to omit the demon of the title. A veteran of the Val Lewton school of horror filmmaking, he preferred to let the audience’s imagination fill in the blanks. The insertion of the titular demon into the film, particularly its insertion at the beginning of the film, where it becomes a literal element of the plot rather than an enigma, almost undoes the theme of the movie. (The appearance of the demon in this film is somewhat controversial, a point to which I will return). The film begins with a montage of the epicenter of British superstitions, Stonehenge, and intones in voice-over that devil cults have existed since the beginning of time and persist unto the present day. This works a tidy magic trick of its own: it suggests that Britain’s pre-Christian past is Satanic and suggests that Christian magic and pagan magic are at odds with one another to this very day. It’s worth noting at this point that in spite of Tourneur’s metier in horror movies and film noir, he is at his core a Christian filmmaker (a fact on display in the overtly Christian The Stars In My Crown). This is significant because Curse of the Demon is a film about superstition by a believer in one kind of supernatural world, though it is by no means the only filter through which one should view the film. But I digress. After the opening credits, we are introduced to the unfortunate Professor Harrington, driving through a forest at night to a rendezvous at the estate of the cherubic Julian Karswell. Trees play a significant role in the overall design of the Curse of the Demon. The film places panicked characters in the darkest part of the forest whenever its more sinister supernatural forces are pursuing them. Harrington is one such character. When we meet him, he constantly looks up into the branches of the overhanging trees as he drives under them. Harrington is in a panic. Karswell has called…something…to terrorize the professor and the professor implores him to call it off. In this first scene, Tourneur is already pitting contradictions against each other. Karswell’s library is where he is most often seen in his own home. Ken Adams’s production design is a study in contrasts. The architecture of Karswell’s home is neo-classical. The shape of the space is round, but the floor is rectilinear--geometric shapes in the shot compositions of the film play an important thematic role in Curse of the Demon. With its serene Ionic columns and pedimental door moldings, the space suggests a place of classical order--a temple perhaps--but these flourishes are appointed with the paraphernalia of the occult. The painting over Karswell’s hearth is--I believe--Goya’s "Witch’s Sabbath," for example. There is also the figure of Karswell himself as played by Niall Mac Ginnis. Karswell is the film’s villain, but he is also its most sympathetic character. He is urbane, gracious, polite, and witty. He’s more of an imp than a devil, and the filmmakers have decked him out to suit. Mac Ginnis is a round actor, and that roundness is accentuated by a demonic beard. The character seems to be based on Aleister Crowley, but later in the film, he is presented as a clown and a mama’s boy. This is all a stark contrast to the character one finds in M. R. James’s "Casting the Runes," upon which the film is based. In the story, Karswell is the sort of character that torments children for his own amusement, and as a means of keeping them the hell off his property. The film’s attitude towards him is articulated by the character of Dr. Kumar, one of the scientists: "(The Devil) is most dangerous…when he’s being pleasant." Harrington’s demise at the hands of the demon follows, and while in the overall design of the movie, the scene is a misstep, there’s no denying that that the demon itself is a striking visual. We first see it as an amorphous cloud, perhaps tearing the veil between its own reality and our own. Then we see its silhouette, backlit by fire and smoke. Eventually, we get a close-up. As special effects go, it’s one of the best of its era and distinct from the monsters filmgoers had seen in the films of Ray Harryhausen, for example, or in the contemporaneous "Big Bug" movies. The special effects crew eschewed Harryhausen’s stop-motion animation in favor of a cleverly photographed rod puppet. In general, the effect is convincing. Sidebar: "It's in the trees! It's coming!" After Harrington's demise, the film then turns its attention to its ostensible hero, Professor Holden, played by Dana Andrews. We meet Holden on an airplane, where he is struggling to get some sleep. We also meet Professor Harrington’s niece, Joanna, played by Peggy Cummins. Holden’s arrival at Heathrow provides a visual counterpoint to his personality. An arch skeptic, we first see him in settings where superstition and the supernatural have been banished. Heathrow is a thoroughly modern space--a glittering monument to the jet age--and Holden is surrounded by straight lines and bright lights as he holds court with the press. In his first scenes in London, Holden outlines a hard-core skepticism that admits no possibility of the breath of other worlds. "All good scientists are from Missouri," he says a little later in the film, "they should continually be saying ‘show me.’" "And if you are shown?" his colleague asks. "Then I’ll look twice." One side-effect of presenting the demon so early in the film is that it presents Holden as pigheadedly hidebound in his skepticism--the audience already knows what’s behind everything, and because we know, Holden seems willfully dense in the face of the evidence. The setting of his initial introduction, and the firmness of his position on all things supernatural, is placed deliberately far from the reality the film presents. This is a striking contrast to Joanna Harrington. She’s a kindergarten teacher who chides Holden at one point that "You can learn a lot from children. They believe in things in the dark until we tell them its not so. Maybe we’ve been fooling them." In a lot of ways, Ms. Harrington is a better scientist. She trusts her senses more than Holden does and comes to the correct conclusions far sooner. For all his talk of the world as described to him by his own senses, he trusts his reason far too much. He’s the sort of scientist who scoffed at Galileo when Galileo claimed that falling objects of different weights fall at the same velocity: reason suggests that a heavier body would fall faster, but reason is dead wrong when presented with the wrong sets of assumptions. Holden is slow to grasp that. Holden’s first encounter with Karswell takes place in a bastion of reason: the library at the British Museum. The visual cues in this segment are suggestive: like Karswell’s library, the space of the library is round. Just as Professor Harrington approached Karswell’s manor through an iron gate, so does Holden approach the museum through a similar gate. And when Holden is seen entering the rotunda of the library proper, the shot is a panoramic overhead shot in which it appears that Holden is entering a maze. From here on, Holden will be framed by different geometries than the "reasonable" geometries of Heathrow and the Savoy Hotel. The railings at the museum, for example, are rectilinear shapes that have been violated by curves. These shapes find an echoing shot later in the film when the planks and panels of a door are violated by the curving shapes of a ward against hexes. Also: once Holden has entered the maze, metaphorically speaking, his actions become increasingly bounded by corridors. Holden’s first conversation with Karswell is pleasant. Karswell offers Holden a book from his library and gives Holden his card. He also passes Holden a parchment with runic symbols drawn upon it. Karswell’s card informs Holden that he has a "time allowed." When Holden looks at Karswell as he retreats down a corridor, his vision begins to waver. Holden is formally introduced to Joanna Harrington in a short scene at her uncle’s funeral. She then meets him back at his hotel where she attempts to convince him that there are forces behind her uncle’s death. In this scene, the movie sets her up as an alternate protagonist and as a different kind of rationalist. She bristles at Holden’s condescension and asserts her own intellect when she announces that she, too, had studied psychology. This sets her up as a direct parallel to Holden, one who is more open to the face value of the evidence placed before her, unencumbered by scientific cant. These scenes also find Holden feeling the effects of the hex placed upon him, though he denies it. This gives Tourneur the opportunity to directly contrast Joanna with Holden, by giving her dialogue that directly contradicts Holden. When Holden claims that it’s cold, for instance, she says that it’s hot. Tourneur offers another visual repetition as Holden and Joanna approach Karswell’s estate in the next scene, as the composition echoes Holden’s approach to the British Museum. Karswell is in his element in this sequence, indulging in a flair for the theatrical as Bobo the Magnificent, entertaining the village children and conjuring a wind storm for Holden’s benefit. The object of Holden and Joanna’s visit to Karswell is a rare book, which is emblematic of one of the movies minor themes: writing has power. Holden punctures this notion earlier: "Runic symbols are one of the oldest forms of alphabet…They’re supposed to have magic powers. They don’t." Of course, in the context of the movie, he’s dead wrong. The movie reinforces this idea by setting many of its confrontations in libraries and by placing large parts of the exposition into diaries. The sequence at Karswell’s children’s party also introduces the viewer to Karswell’s mother, who plays a pivotal role later in the movie as she tries to mediate between Karswell and Holden. She dotes on her son, and wants nothing more than to see everyone satisfied. Both Karswell and Holden dismiss her: Karswell thinks she is a fool, Holden thinks she is a pawn of her son. Despite the foolish, Margaret Dumont-ish portrayal by actress Athene Seyler, Mrs. Karswell eventually proves to be wiser than the film’s antagonists. Mrs. Karswell’s attempts to dissuade Holden are half of the film’s plot in the second half of the movie, culminating in a séance where Joanna is convinced of her uncle’s presence and Holden is convinced he’s witnessing theater. It does, however, provide Holden with the key that unlocks his skepticism in the film’s most famous line: "It’s in the trees! It’s coming." Karswell’s mother also offers a foil for Karswell himself, in a scene where Karswell laments that he’s just as trapped as his followers and that without exercising the rule of fear upon them, he would be just as vulnerable to the forces they have unleashed. The film’s other plotline is the investigation of Rand Hobart, suspected of murder in relation to Karswell’s cult, but in a catatonic state in the aftermath. This investigation takes Holden to Hobart’s family and community, away from the ivory tower of the academy and into a world of superstition and ignorance. In this thread, we find out that Holden himself has been marked by the parchment that has been passed to him, causing him to look more carefully at it. This takes him to Stonehenge and Britain’s pre-Christian past, where he finds the runes passed to him inscribed on the stone dolmen. The various threads of the plot come to a head when Holden and his colleagues finally examine the unfortunate Rand Hobart under hypnosis. Hobart, like Holden, was chosen by the parchment. Unlike Holden, he knows what awaited him, and passed it back. Hobart repeats the line, "It’s in the trees!" which is exactly the evidence that Holden needs to enable him to peek behind the veil of his perceived reality. Hobart’s testimony gives Holden the means to challenge Karswell on his own terms, framing a final battle of wits in which Holden must contrive to pass Karswell the parchment without him knowing about it. The irony of all of this is that Holden arrives at superstitious belief through the reason and investigation, though even at the end, he maintains a certain incredulity about Karswell’s ultimate fate. "Maybe it’s best NOT to know," he tells Joanna at the film’s end. 3.

The film’s fame has been perpetuated through a number of conduits. Carlos Clarens’s seminal study of the horror movie, An Illustrated History of the Horror Film used the film’s demon on its cover. Clarens notes that Curse of the Demon was released as the second half of a double bill with Hammer’s The Revenge of Frankenstein, "which, in a wink, it eclipsed." The film gained a different kind of fame as one of the eleven films mentioned in "Science Fiction Double Features" in The Rocky Horror Picture Show. It gets the song’s best lyrics, to boot: "Dana Andrews said prunes, In the following decade, Kate Bush sampled the line "It’s in the trees! It’s coming!" for The Hounds of Love. Curse of the Demon’s influence on the films that followed it was modest, but the films that DO show that influence are a distinguished bunch: The Innocents and The Haunting (directed by fellow Lewton alum Robert Wise) are the most obvious followers. The film that most closely resembles Curse of the Demon is Sidney Hayers’s Burn, Witch, Burn (aka: Night of the Eagle), which is its thematic twin. The second version of Fritz Leiber's Conjure Wife, Burn, Witch, Burn echoes Curse of the Demon point by point, following an academic whose rational worldview crumbles as he comes to realize that there is witchcraft behind the departmental politics in which he finds himself embroiled, and that his wife is, herself, a practicing witch. The signature image from the film finds the film's lead, Peter Wyngarde, backed against a blackboard on which is written "I do not believe," with Wyngarde's body blocking the word "not." Further reinforcing the link between the two films is the similarity of their original British titles: Night of the Demon and Night of the Eagle. The two films make a formidable double bill. But perhaps the film’s most obvious influence is its willingness to show the audience its monster and its reliance on special effects. It inherits this from the science fiction movies of its day and spreads it to the gothic horror film, for better or worse. Acknowledgments: Goya: "The Sleep of Reason," reproduced at the head of this page, is the 43rd plate in Los Caprichos, a series of etchings and aquatints Goya printed in 1797 and 1798, a time when the Enlightenment was being imposed on Spain by France at the point of a bayonet. Like Curse of the Demon, the image is a collision of reason and superstition. The dreaming figure is thought to be a self-portrait of the artist himself. Romantic art in opposition to The Enlightenment makes an appearance in The Curse of the Demon at a couple of points. I’ve already noted the Goya in Karswell’s study. One of the demons presented in the various papers and books in the film is William Blake’s Great Red Dragon. A lot of my thinking about the role of geometry in the film’s production design has been suggested by Michael E. Grost’s website, The Films of Jacques Tourneur. Grost puts the visual design of the movie into the context of Tourneur’s other films. I draw different conclusions based on the horror film’s roots in expressionism. Some general thoughts on the conflict between Holden and Karswell were suggested by Liz Kingsley’s And You Call Yourself a Scientist… Other sources: Jackson, Shirley, The Haunting of Hill House, 1959, The Viking Press, New York, pg. 1. Clarens, Carlos; An Illustrated History of the Horror Film, 1967, Capricorn Books, New York, pp. 144-145. Curse of the Demon was cut down by 13 minutes from its British incarnation as Night of the Demon for the American market. The current DVD edition of the film presents both versions, but its promotional copy lies about its provenance. It claims to present the film in its fully restored version for the first time on video, but the version of the film released on VHS was the original version. It is, however, the first time the cut version has been available on home video in any format. Curse of the Demon is available in the United States on a Sony DVD from most online home video retailers.

Curse of the Demon, 1957, directed by Jacques Tourneur. Dana Andrews, Peggy Cummins, Niall MacGinnis, Maurice Denham, Athene Syler, Liam Redmond, Reginald Beckwith, Rosamund Greenwood. Screenplay by Charles Bennett and Hal E. Chester, based on "Casting the Runes by M. R. James. Cinematography by Ted Scaife. Production design by Ken Adam.

10/12/06. |