Suspense

Index

Act of Violence , 1948, directed by Fred Zinneman. Van Heflin, Robert Ryan, Janet Leigh, Mary Astor, Phyllis Thaxter, Berry Kroeger.

Synopsis: War hero Frank Enley is living the American dream. He has a wife who adores him, a young son, a thriving business. He's helping build the post-war world with his contracting company. Unfortunately, he has a deep, dark secret, and one day, that secret shows up on his doorstep in the person of Joe Parkson. Parkson was Enley's gunner in the war and his fellow POW when they were shot down. And he has a grudge against Enley, one he plans to settle with an automatic pistol. Frank gets wind of Parkson's presence before he can be confronted with his past. He does the sensible thing, and flees, hiding out first at home, then at a builder's convention, where he confesses his sin and his hypocrisy to his wife, then vanishes to drink his way into oblivion. Eventually, he descends into the underworld, where a tired bar hooker puts him into contact with the means to eliminate Joe for good, not realizing that he'll never be free of his past once the die is cast.

The Language of Film Noir: I've never been a fan of director Fred Zinnemann--I've always thought he was a bit...dull, actualy--but Act of Violence is a film that makes me rather reconsider. This film is so precise in the way it deploys its symbols and in the way it uses the iconography of the crime films of the day that it makes me wonder if what I've always thought of as stodginess in Zinnemann's films isn't actually classical elegance. The film opens with a sequence of symbols that maps out its terrain with a laudable simplicity:

We open with a lamed man retrieving a gun:

The camera tilts upward to reveal Robert Ryan as the agitated man. At this point, we don't know if he's the hero of the piece or the heavy. Ryan's screen persona, based on previous roles, can go either way:

Then comes the classic noir image: Night and the city, and a lone man to face it:

We follow Ryan to small town America. We suspect that he's the rock that will disrupt the placid pool. The image of Ryan, a determined, armed man, contrasted with a Memorial Day parade has one meaning at the outset--he's chaos amid order--but will take on another meaning late in the movie. This is the sort of thing that Hitchcock did all the time, but Hitch never detonated the image later in the movie the way this film does:

Soon after, we are introduced to the film's "hero." When we first see him, he's smiling with his toddler son on his shoulders. The movie is slanting our perception of Frank Enley from the outset. War hero. Family man. Builder of the future of America:

We are also shown the future being built. This image reminds me of similar images in John Ford's westerns, in which The West is being built as a symbol of American peace and progress. Zinnemann, an Austrian expatriate who fled the Nazis appears to have a different take:

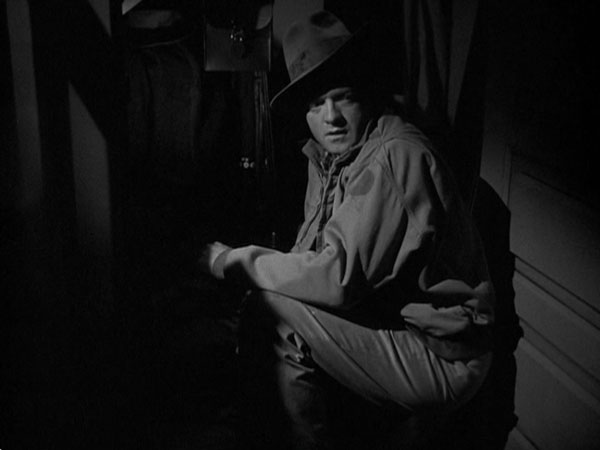

And so, the film has mapped out the postwar dream with a few deft strokes, set up its central conflict between Robert Ryan's Joe Parkson and Van Heflin's Frank Enley, and has done so without so much as a hint of their underlying conflict. So far, everything is slanted towards a fairy-tale image of postwar prosperity, so it comes as a bit of a shock when everything gets inverted as the movie unfolds. The language of film noir is useful here, too. After we become aware that Frank may not be the war hero the film has led us to believe he is, we get this mise en scene, in which a crouching, seemingly cornered Frank is bounded by shadows...

...and in which he stands up to be engulfed by them. To become a shadow:

This is a neat trick. From that point on, the film becomes an exercise in critique of the cost of the American dream, made just as that dream began to unfold. White becomes black. And we join Frank on the downward spiral.

The film is loaded with other symbolism, too, though much of what I attach to it may not have been intended by the filmmakers--as the ones ennumerated above surely are. I've long held that film noir is the conjoined twin of the horror movie, and Act of Violence, is a superb case in point. David Skal's wonderful book on horror movies, The Monster Show, offers one explanation of the obsession with deformity among the horror movies of the 1920s and 30s as a reaction to the disfigurment of the veterans of the first World War (the living end of this is found in both of Abel Gance's versions of J'Accuse). This iconography reappears in a different form in Act of Violence. Robert Ryan's limp casts him as a monster of sorts. In the film's early going, the limp, and the sound of his gait, is played for terror. We hear it outside as Janet Leigh's threatened housewife tries to shut out it out. As a lumbering chaos, Ryan's character is a cousin to Frankenstein's monster. For that matter, Van Heflin's descent into degradation is not so very far off a Tod Browning/Lon Chaney melodrama.

By the time Frank begins his dark descent, Ryan's character has changed aspects. Rather than a chaos, come to disrupt the order of Frank's idyllic existence, he becomes a Fury, hounding him with his own guilt. Its final expiation is one element that tends to remove the film from the universe of noir. In film noir, there's usually not redemption at the end of the road, but here, there is. True, it is a fatal kind of redemption, but it's a redemption that touches both of the film's antagonists.

8/04/07